This question has been on the frontier since Philips introduced the Full HD Cinema 21:9 56PFL9954H back in 2009. An audacious piece of tech, it shrugged off the 16:9 HD standard.

This TV presented a cinematic widescreen panel, finally putting an end to the letterboxing we had to endure while watching cinematic movies.

Fast forward to the present day, and the idea of an ultrawide TV doesn’t just seem cool but feels more relevant. The home has become the new cinema; with most of us staying indoors and movie theaters seeing little footfall, the prospect of an ultrawide screen resonates with a growing appeal.

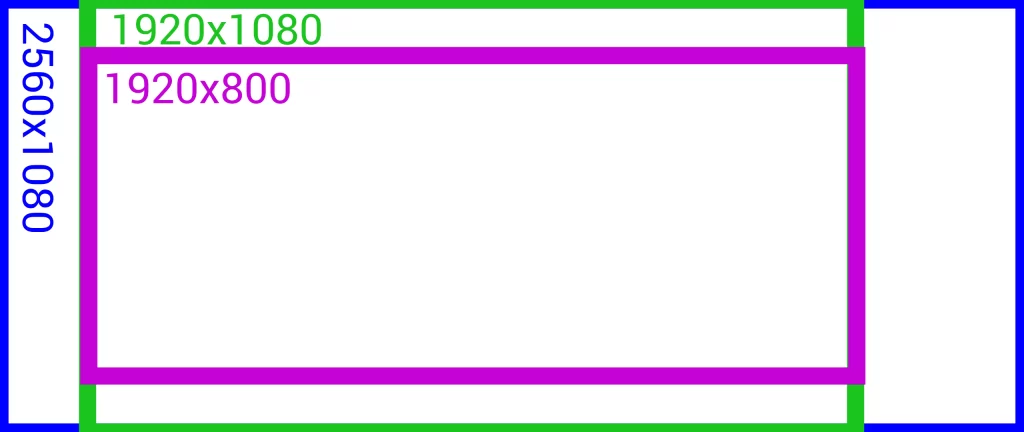

The technology behind the 21:9 Philips TV was intriguing. It was designed with a 1080-pixel tall screen to ensure that 16:9 Full HD footage retained its full resolution, creating black sidebars for regular video content, essentially mimicking a smaller 50-inch set. The magic happens when viewing cinematic content. The TV would upscale the original 1920×1080 image to 2560×1440, cropping off the top and black bottom bars to deliver a cinematic viewing experience. The upscaling, even by today’s standards, worked well.

Not without flaws, but that was an example of ultra-wide TV that works as it should. And I remind you, that was the year 2009 around. And yet, it remained something like a dream, a promising project that was never launched to the new market niche or created: a one-time experiment with no promising results.

The present state of things

Fast forward to today, and we find ourselves amidst a technological era where upscaling and processing have become so advanced that ‘native’ resolutions are starting to lose their once-critical importance. 4K gaming consoles regularly upscale lower resolution frames; 8K TVs deliver better image quality despite the lack of 8K content.

In this context, the 21:9 Philips TV’s approach to upscaling makes perfect sense. In fact, a modern version of the TV, equipped with a 5040×2160 screen and AI-based processing, would unquestionably offer an even better-than-4K viewing experience.

However, the concept of ultrawide screens hasn’t remained limited to TVs. Over recent years, we’ve seen the 21:9 gaming monitors, and they’ve taken their niche. But despite the growing appeal and proven advantages, ultrawide TVs remain conspicuously absent from the market. One might wonder why.

The reasons are not far to seek. To begin with, producing ultrawide TVs would be significantly more expensive. The costs would invariably trickle down to the consumer, limiting the prospective buyer list to a niche audience of enthusiasts and those who put the ultimate cinematic experience over cost.

Technical limitations

One crucial aspect lies in the disparity between 21:9 panel resolutions and 21:9 content resolutions. Currently, the maximum horizontal resolution for ultrawide video content (be it BluRay, streaming, etc.) is set at 1920 pixels.

For instance, to maintain a 1080p standard, a large-screen 21:9 TV would likely need to have a 2560×1080 resolution. This would allow for playing 1920×1080 content natively while applying pillarboxing, essentially adding vertical black bars at the sides of the video. While manufacturing such a panel would not require significant re-tooling of the production process, it would require content to be scaled up to fit the screen. Scaling up invariably degrades quality; thus, it’s not the best solution.

Another option would be to make a 1920×800 TV, which would involve creating a non-standard 800p panel to display 21:9 content natively and down-scaling 1920×1080 content. This process of down-scaling, also known as supersampling, generally yields better image quality than up-scaling. However, 800p is not an industry standard, and re-tooling manufacturing processes for it makes no business sense. It will increase costs and put them on the end-costumers, making such TVs more expensive than competitors with a standard 16:9 aspect ratio.

Similarly, at the 4K level, we could consider a 3840×1600 output for 21:9 content with downscaled 16:9 content from 3840×2160 to around 2844×1600. However, manufacturers are unlikely to invest in re-tooling for large-format 1600p panels suitable for 50”+ TVs unless the format becomes standardized and there’s a surge in 21:9 content from both the TV, streaming, and film industries. The most practical solution for a manufacturer might be a 5040×2160 panel. Still, that would mean upscaling 21:9 content, as it’s unlikely to start being rendered at a horizontal resolution of 5040.

So while there are technically feasible paths to creating ultrawide TVs, each comes with narrow challenges: high production costs, limited content availability, and non-standard resolutions pose significant hurdles.

It’s a tall order, requiring a joint push from both manufacturers and content-makers (take into account that it’s not just about the film industry but coordination between TV, streamings, and studios). Given the costs and the risks, it’s understandable why TV manufacturers are playing it safe, sticking with industry standards, and targeting the broadest possible market. Ultimately, making ultrawide TVs a mainstream reality or even granting them a solid niche will take more than deep pockets.

Maybe that’s time for other TV formats?

Despite the cost constraints, the concept of ultrawide TVs remains as tantalizing as ever, especially when considering the possibilities offered by new display technologies. One of them is rollable TVs. Currently, that’s an ultra-niche thing, but what if we have a TV that’s rollable not vertically but horizontally, adding panels to fit the ultrawide content without black bars? Sounds interesting.

Take a cue from LG’s rollable OLED R screen. LG announced that it could extend to different heights to fit different content types. While it doesn’t currently support different aspect ratios, it doesn’t seem too far-fetched to imagine future versions that could do just that.

The one question is: for what? Great technology can still fit any content with any aspect ratio – home projectors. This technology is evolving and seems like a solution to the ultra-wide content problem. The only pitfall is that it requires a special place (or at least a lot of space) to be used as a projecting surface.

The content is the problem

While cost and market demand are real concerns, content is another significant obstacle in the way of ultrawide TVs. Most of the TV broadcasts and a significant amount of content available on streaming platforms adhere to the 16:9 format. Even though an ultrawide TV would enhance the cinematic viewing experience, it could distort content all of us used to watch: Netflix, ESPN, TV shows, Hulu, and many, many others.

For instance, consider the LG 29LN450W 21:9 29″ Ultrawide TV. This model, marketed as a TV with computer monitor capabilities, operates much like a monitor with TV features. Its 21:9 aspect ratio brings headaches when handling TV broadcasts.

When you watch any HD signal on this TV, you get black bars on each side of the screen or need to ‘stretch’ the image to fill the available screen space. The latter leads to distortion, akin to watching standard definition on an HD display. While the 21:9 format finds ample application in computer usage, it doesn’t lend itself well to the current standards of TV content. And it seems that the film industry isn’t that power that may challenge the state of things, especially when film studios themselves are trying to integrate their content into streaming.

This brings us back to the original question: Why are there no ultrawide TVs yet?

Ultimately, the challenges outweigh the benefits. The production cost, niche market, and content pose significant hurdles. Yet, the dream persists. Who knows? Maybe the next big leap in home cinema is just around the corner. But I’m not sure. At least it shouldn’t be about TVs,

Of course, an ultrawide TV that strikes a balance between cost, demand, and content compatibility might well be on the horizon. And if you’re dreamin’ about an ultra-wide TV screen, you can only hope, wait, and watch.